Back to Buxton

When I drove over the last hill, and saw the Ghaap escarpment, signaling my final approach to the edge of the Kalahari desert, I smiled. I knew that my six hour drive from Johannesburg to Taung was nearing its end. The South Africa I had known had changed. New signs along the way pointed to “Taung Skull,” as if one could actually see the famous fossil. Many of the familiar dirt roads I had traveled so often were now paved, and I saw evidence from a few new houses that at least a modicum of prosperity had reached the Taung area, even if extreme poverty was still the norm.

I finally arrived at the gate that had been constructed when Taung became a Bophutatswana National Park, back in the days of South African apartheid. But a guard would not let me in, saying that the site was closed. “They are doing some things,” she said. I asked if would be open tomorrow, and she replied that she didn’t know the date, but it would not be tomorrow. I said I had come a long way, from the United States, yet she wouldn’t budge, as she stared off into the sky. People here do their jobs well. And, I noted, it was only second time I had seen a woman in this village playing such an important role outside of household duties.

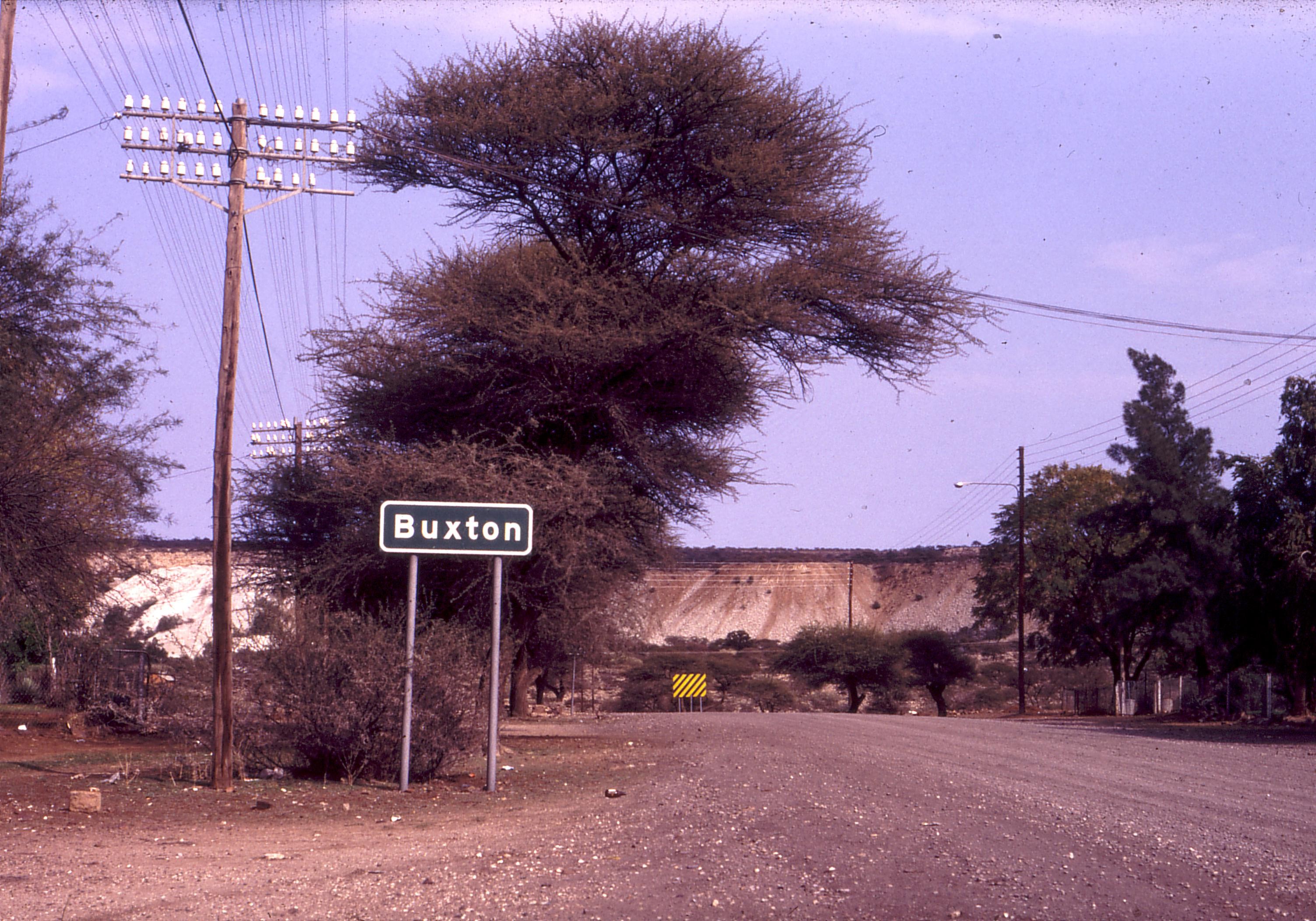

But no matter who was in charge, there was no stopping ‘Mr. Jeff.’ I was familiar with all sorts of hassles in this region, and knew this site like the back of his hand. So I just drove up the back way, toward the village of Thamasikwa, and found a place to hide my car beyond the fencing they hadn’t finished putting up. I then stepped once again onto the grounds of the ‘Buxton Limeworks,’ where the famous Taung skull had been blasted out of the rock by quarriers in 1924.

With beer in hand, as was my tradition for first arrivals here, I walked toward the fossil site where I had labored along with the locals for seven field seasons of fossil excavations. I had my headphones on with my favorite Taung excavation music, when I heard something. I took the headphones off to discover it was just a donkey. A few minutes later I heard something else, took off my headphones, turned around, and saw somebody. I thought “uh oh, now I’m in trouble ... again.”

I feared I would not be able to access the site, and this entire trip would have been nothing but a boondoggle. Then, the person in the distance shouted “Jeff!” As we got closer, I recognized him as Joseph Leeuw, who had worked for me as a foreman of the locally hired workers at Taung, and had worked at my lab at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. It was an amazing coincidence of fate that we should run into each other at that moment, for we had not seen each other since I left South Africa more than a decade earlier. We had a handshake, and then a big hug. And I felt a great sense of relief that I wasn’t in trouble. Far from it, I was back amongst friends.

He was on his way to visit a friend at Thamasikwa up the road, so we went our separate ways and I ventured around the site, a white moon-like landscape of solidified limedust from when the Buxton Limeworks had been an active quarry. Indeed, the famous Taung skull, a fossilized skull of a child who represented one of our early African ancestors, was a product of that operation.

The excavations I had led here were meant to reveal more about the Taung skull, but in the years I worked there I built up a treasure of personal memories. That evening I watched yet another stunning sunset from the edge of the Thamasikwa river. As the sky darkened, I watched the stars of the Southern Cross appear one by one in the sky. It was then that I decided to share my treasures.