Early History of Taung

Serendipity and Discovery

The fossil boom of South Africa began with the gold boom along the rand. Gold deposits had been discovered near Johannesburg, South Africa in 1884 which led to a thriving gold mining industry. Back then, limestone was used in the processing of gold, and was also needed for agriculture and construction, so a booming limestone industry began. This was wonderful for palaeontology, because fossil caves were associated with limestone caves, and across South Africa many caves were exposed, including those along the Ghaap escarpment such a region known as Taung.

‘Taung’ means ‘place of the lion.’ There are no lions there today, and there is no fossil evidence that there were lions around when a young child of our ancestral lineage got deposited in a remote limestone cave some 2.8 million years ago. ‘Tau’ was the name of the local Tswana chief when the region was named, and ‘ng’ means ‘place of’ in the seTswana language. The region became of significance many years later because of its limestone deposits and the fossils they encased.

So the Taung skull discovery starts not with Raymond Dart, the oft-cited ‘discoverer’ of the hominin child from Taung, but with limestone quarry operations at the Buxton/Norlim limeworks at the southeastern margin of the Kalahari desert. As early as 1919 there had been fossils found at Taung, but one baboon skull began the circuitous circumstances leading to the ‘discovery’ of the most famous fossil from the site.

Raymond Dart’s involvement with the story began with his student and anatomy demonstrator Josephine Salmons, pictured here to the left of Dart at the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School.

Salmons had a friend, Mr. Pat Izod, who’s father had worked at the Buxton limeworks, and she saw an interesting fossil on his mantle that she thought would impress her professor. It was of an extinct baboon, later known by the scientific name Papio izodi, and Prof Dart was impressed indeed. He asked that an other fossils from Taung be sent to him.

One of Dart’s University colleagues was a geologist named Robert B. Young. On a geological survey tour, Young visited the Buxton limeworks at Taung, then called Taungs. There he met with the quarry manager, Mr. A.E. Spiers, who had been saving fossils discovered by Mr. M. De Bruyn. De Bruyn had been blasting out limestone and adjacent fossils from near what is now known as the ‘Dart pinnacle,’ and he was the first to recognize that it was different from the baboon fossils. Thus he was careful to keep the two pieces that fit together. Young crated up the fossils, including the peculiar one that had been sitting on Spiers’ desk, by some accounts being used as a paperweight. The crate was then sent by train to Johannesburg where Dart eagerly awaited its arrival, in late November 1924.

Upon opening the crate, the first fossil that caught Dart’s eye was this:

It is a rock cast from the inside of a skull, known as an ‘endocast.’ Raymond Dart was well-known as an expert on the anatomy of the human brain, so he immediately recognized the gyri and sulci and other brain features of this endocast. But it didn’t look like a baboon skull, as De Bruyn had noted. So Dart reached into the crate and pulled out the matching piece, which was encased in a rock matrix. Over next ‘40 days and 40 nights,’ as the legend goes, Dart used his wife Dora’s steel knitting needs to chip away the rock and expose the face of what was to become the famous ‘Taung Child’.

Scientific Reception of Taung

Before we continue to the controversies of early 1925, let’s recap the ‘discovery’ of the Taung juvenile skull. The true discoverer was M. De Bruyn, quarryman, who first noticed it was something different. Geologist Robert Young then discovered the fossil remains on the desk of the quarry manager. Dart then ‘discovered’ the fossils collected by De Bruyn in a crate shipped to him from Young. But the whole sequence of events was started by Josephine Salmons, who went on to become among the first female medical practitioners graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School.

Dart’s first publication of the Taung skull as Australopithecus africanus was on February 7, 1924, in the British journal Nature. Although the name translates as ‘southern ape of Africa,’ Dart suggested that it was one of our ancestors who stood up on two legs. Though all were intrigued, it met with a great deal of skepticism. Due to its juvenile status, some suggested that it was young ancestral chimp. Others even derided Dart for mixing Latin and Greek in the species name. Finally, estimates of its geological age varied wildly, making it difficult to establish it as an ancestor.

Another deterrence to the acceptance of Taung was its geographic origin. At the time there had been the discoveries of Homo (Pithecantropus) erectus in Indonesia, so many suspected our ancestry was Asian. British scientists of course knew that we had come from an alleged species Eoanthropus dawsoni, represented by a ‘skull’ from Piltdown, England, which later was demonstrated to be a hoax. Nobody suspected that our earliest ancestors came from Africa, and especially not from what Dart called “the arse-hole of Africa.” But they had forgotten their Darwin, who in 1873 wrote:

“In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is therefore probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man's nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere.”

On the occasion of Dart’s 95th birthday, this author had the privilege of meeting a still feisty Raymond Dart who exclaimed “Darwin said that man evolved in Africa, and I proved it!”

The first scientist of note to visit Taung after the1925 publication was Ales Hrdlička, an American scholar born in what is now the Czech Republic. He had founded the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and was on a global tour that landed him in South Africa. At the site, in August of 1925, with the limestone quarry still active, he chipped away at some sandstone ‘breccia’ deposits of some ancient caves. There he discovered some fossil cercopithecid remains (probably extinct baboon), but felt he was doing more harm than good. The fossils he found were allegedly placed in the British Museum of Natural History, but as of today nobody knows their whereabouts. The deposits however are now known as the Hrdlička deposits, which is a series of former caves, richly filled with numerous fossil bones, mostly of extinct baboons.

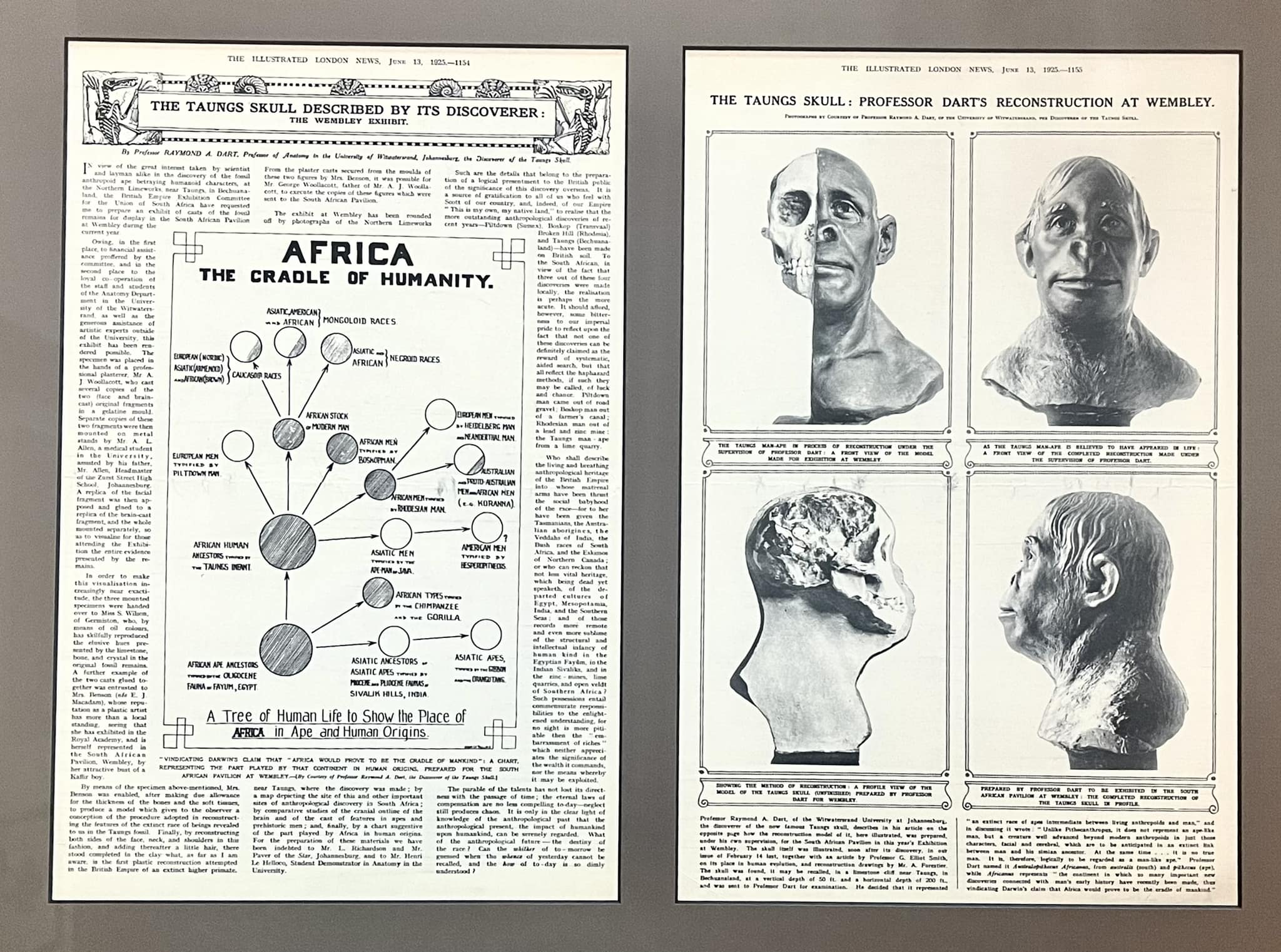

That same year, Dart commissioned a sculptor to do a reconstruction of the Taung child, that was exhibited in Wembley, England. Here it is as portrayed by the Illustrated London News of June 12th, 1925.

In order to garner support for his interpretation of the Taung skull, he took the fossil to London, giving him a chance to meet with his then wife Dora, who had been doing medical training there. He arrived in 1931 on February 7th, six years to the day of the first publication in Nature. But the same people who had published against Taung’s status as a human ancestor were not swayed by his presentation, original Taung skull in hand, to the Zoological Society of London. By Dart’s own account, his presentation fell flat.

To add insult to injury, Dart’s full written description of the fossil got rejected, and remains unpublished to this day, save the parts on the dentition. Instead, Arthur Keith published a description in 1931 book, in which he dismissed Taung as a human ancestor, relegating it to the ape ancestry.

One scholar who had vacillated from partial acceptance to complete rejection was Grafton Elliot Smith, an Australian mentor of Dart. Dart had to return to South Africa but left the skull in the hands of Elliot Smith for further study and casting of the remains. It was arranged that Dora Dart would return with the fossil after she had completed her medical studies. So before her departure for home, Dora dined with the Elliot Smiths at their home, and Grafton saw her and the Taung child to her hotel in a taxi, which he dismissed in order to say goodbye in the hotel lounge. Later that night, after undressing in her room, Dora was petrified to realize that the fossil was not with her. Thus the Taung skull had an unexpected joy ride around London, alone in the back of a cab. Fortunately the fossil was turned in to the police by the cab driver, and retrieved by Dora and Elliot Smith at 4:00 AM. There is little doubt that this episode contributed to the divorce of the Darts in 1934.

Research at Taung continued only sporadically. The first serious attempt at revealing the nature of Taung was made by scholars from the University of California. Ironically, the team was first shown the site by Raymond Dart in what was putatively his first visit to the Buxton Limeworks in 1947.

An American geologist named Frank Peabody stayed for a year, conducting the definitive research on the limestone tufas and excavating fossil baboon bones from the spot where Ales Hrdlička had found similar specimens so many years before. Peabody searched rigorously for the immediate relatives of the Taung child, with the courtesy of the quarry manager who would use dynamite to blast out blocks of fossiliferous rock for him. But as Peabody's field notes reveal over and over again, "No sign of Aust."

Again, aside from occasional visits by curious scientists and an excavation of Equus cave in the same limeworks, rigorous work on the Taung skull site did not resume until 1987. Meanwhile, discoveries of adult remains of Australopithecus africanus at the South African sites of Sterkfontein and Makapansgat, confirming the species as a small, upright and bipedal hominin and one of the roots of our family tree.