Taung Skull Features

The Taung Juvenile Skull from the Buxton Limeworks of South Africa is the type specimen of Australopithecus africanus, a late Pliocene and/or early Pleistocene hominin.

A full description of the skull was written by Raymond Dart, but never published. Following is a brief description with the essentials:

The exposed skull comprises three primary elements: 1) An endocast of the right and partial left neurocranium; 2) The upper face with a partial forehead, nearly complete orbits, nasal aperture, full right and partial left zygomatic arches, and complete alveolar process with ten deciduous teeth and two emerging permanent first molars; 3) A mandible with a body and partial rami, with an alveolar process encasing ten deciduous teeth and two emerging permanent first molars. (Note: part of the right mandibular ramus, including the mandibular condyle and coronoid process remain attached to the upper face.)

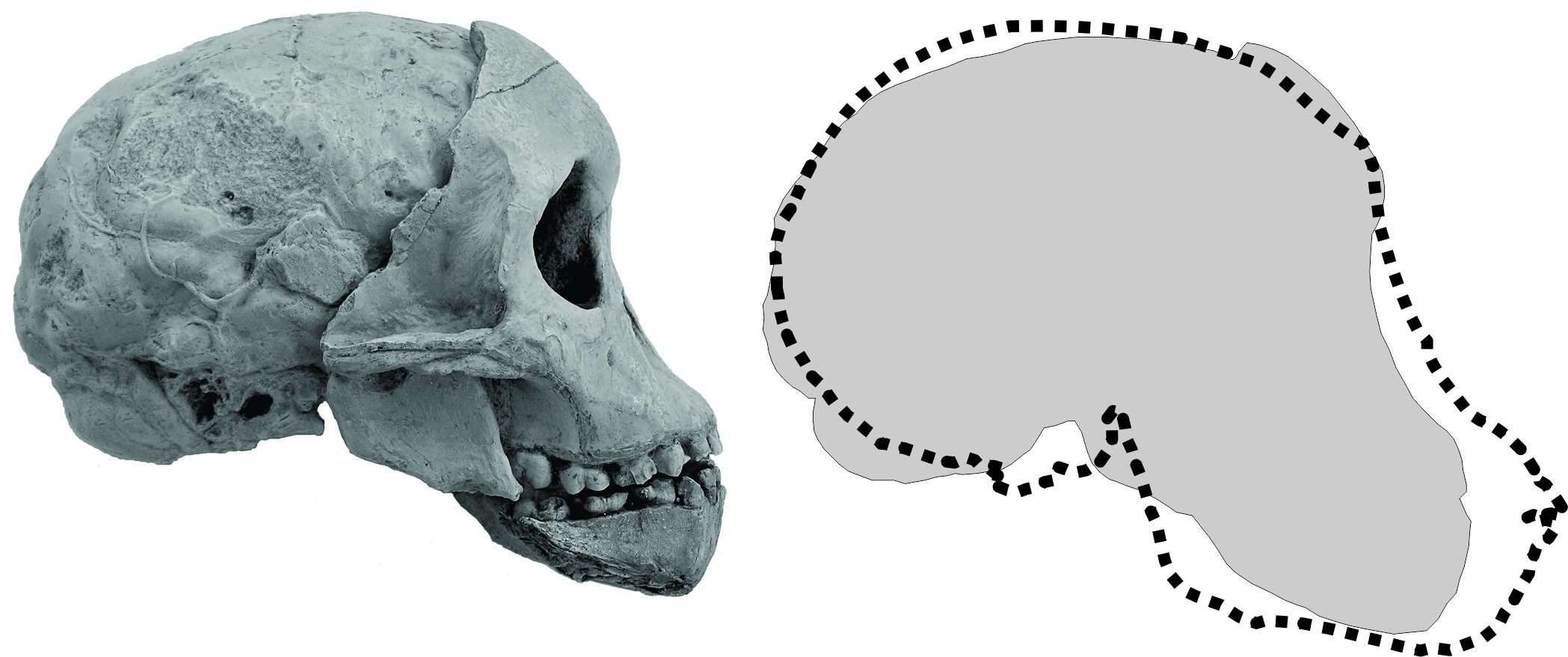

The posterior or deep part of the face fits the endocast perfectly, though some of the endocast matrix remained broken off and left adhering to the frontal bone. So the composite skull in right lateral view appears as below (A). It is here compared in outline to modern skull of a chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes, of the same developmental age.

The Face of Taung

The Australopithecus face of the Taung juvenile is less prognathic than that of a modern juvenile ape, or any Miocene apes, as seen in the illustration above. Dart (1925) claimed that the forehead “rises steadily from their margins in a fashion amazingly human.” Well, maybe not quite, but certainly more than Miocene or contemporary apes. The orbits and nasal aperture are commensurate with juvenile ape proportions, as are the flat and vertical nasal bones.

The dentition show a typical anthropoid complex of deciduous teeth, with the first permanent molars emerging, but not yet into occlusion. There is no canine diastema. The permanent mandibular molars have the typical Y-5 cusp pattern of hominoids.

From CT scans, first initiated by Glenn Conroy (Conroy & Vannier 19**), we have seen the emerging permanent teeth within the maxilla and mandible. This led to the conclusion that the Taung juvenile probably died and got deposited at age 3 or 4.

The Taung Endocast

Before Raymond Dart chipped out the face that posteriorly fit the endocast of the neurocranium, he knew he had something special. The gyri and sulci of the brain were fairly clear, as the developing brain leaves an impression on the inside of the skull. As often said by the great palaeoanthropologist Phillip Tobias, Dart’s successor at Wits, “The brain calls the tune.” So the brain shapes the skull, not the other way around. That is why we can see the gyri and sulci of the cerebrum, the position of the cerebellum, and even an artery that supplies the covering of the brain.

The key to why this endocast was important, and the tip-off to Dart who was an expert in human brain anatomy, was at the base of the endocast. The ‘foramen magnum,’ literally the big hole, is where the spinal cord meets the brain. It was clear to Dart, and every anatomist since, that the foramen magnum was in a remarkably anterior position as compared to other primates. This indicated an upright or orthograde posture which in turn suggested a bipedal form of locomotion.

The brain size, or more correctly the cranial capacity, would have been about 400 cubic centimeters (cc). That is small compared to a human child, but larger than that of a modern chimpanzee of the same developmental age at about 330 cc.

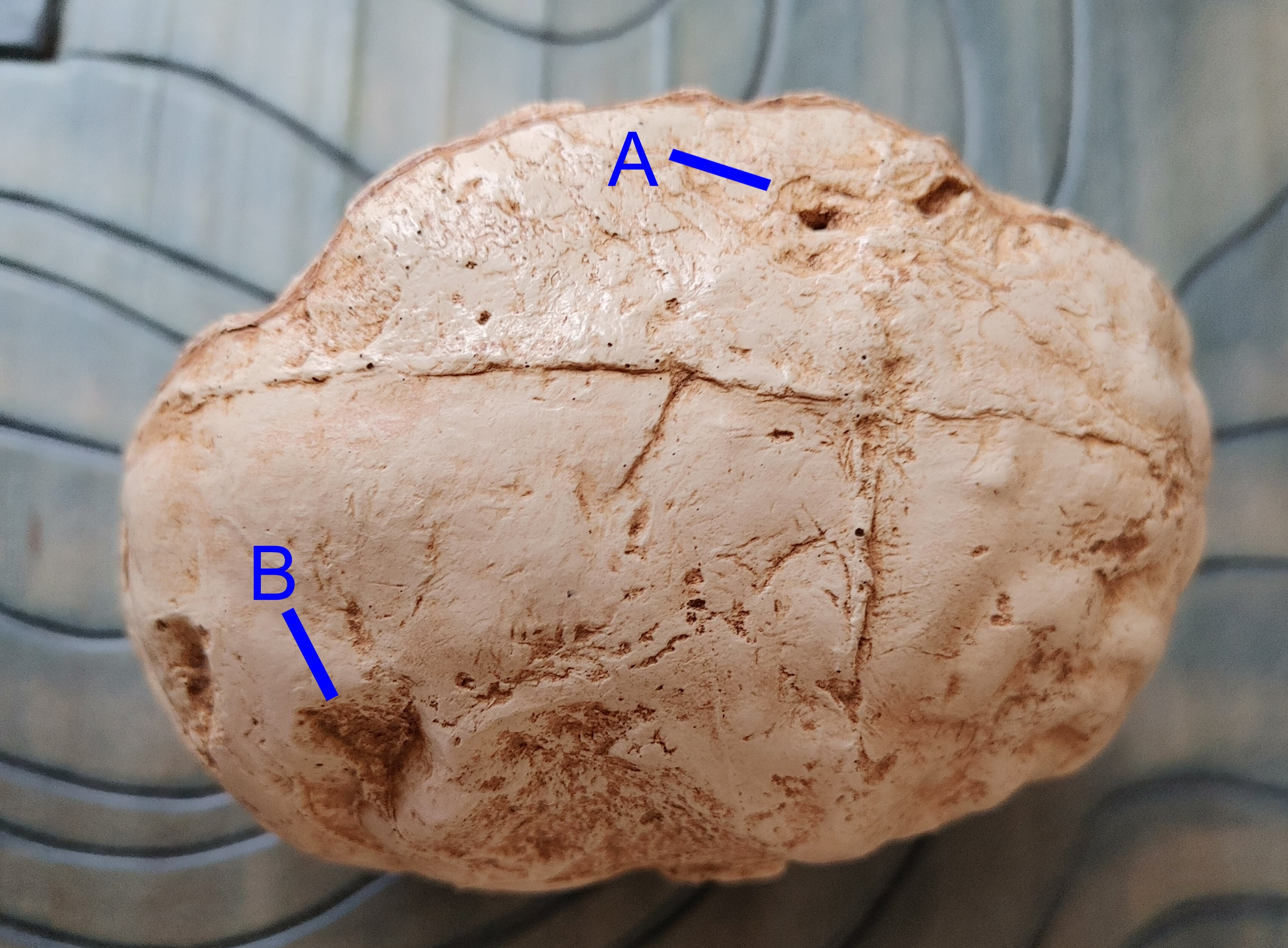

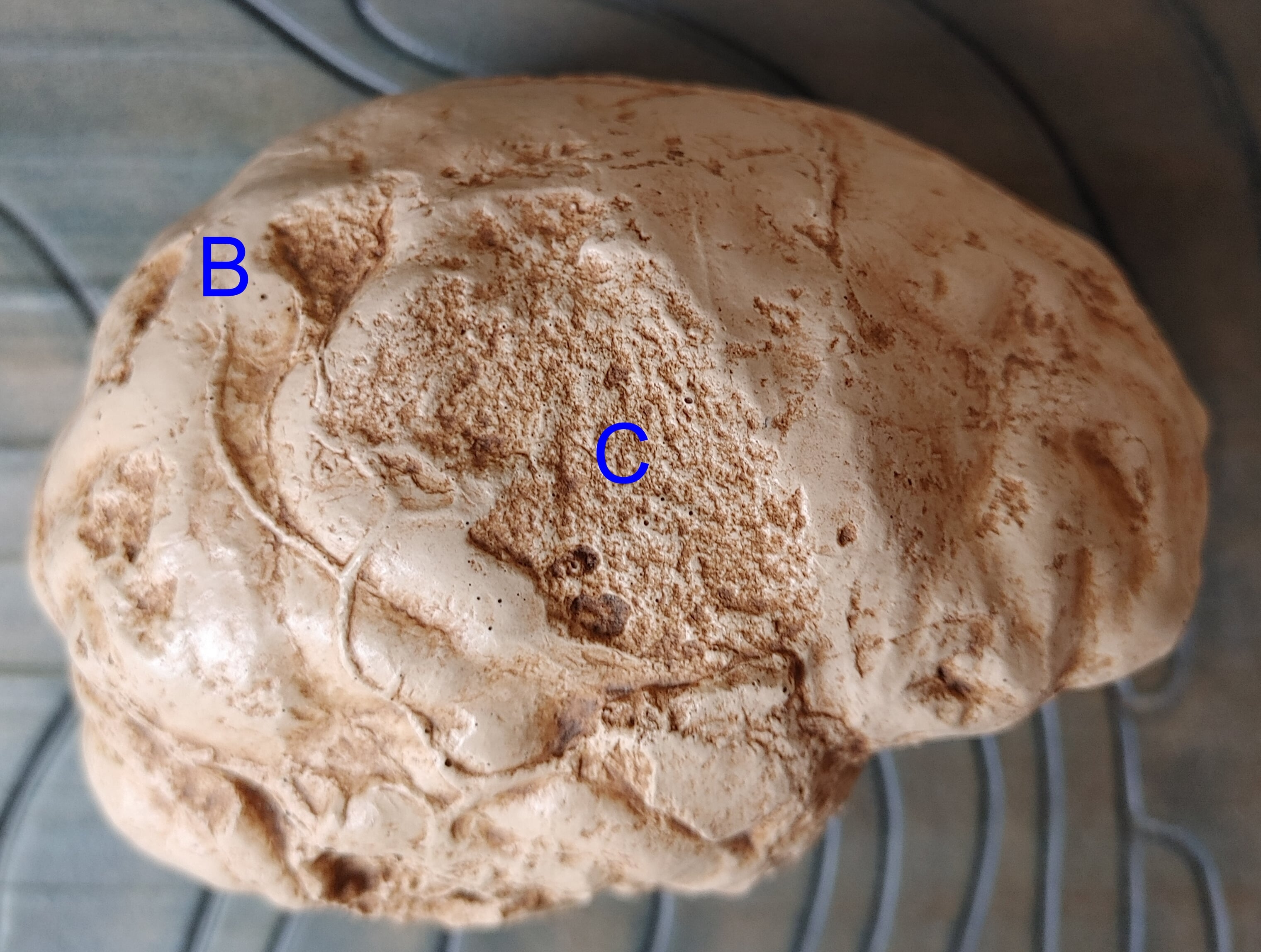

There are numerous imperfections of the Taung endocast, most of which appear to be where the cranial bone did not break cleanly from the endocast (probably when it was blasted from its original deposit). These have a rough surface similar to that of the endocranial break in the frontal region, where a section of matrix adhered to the facial skeleton. These appear at points A and C in the above illustrations. Point A has been interpreted as an indentation caused by an eagle, but is just one of the imperfect castings. Only one point of damage to the endocast, at point B in the illustrations, appears to be the result of a cranial indentation, on the right parietal. This indentation is not diagnostic of any particular predator, though it is consistent with the indentations caused by leopards. It could also be another agent of cranial damage (such as the juvenile biped falling on a rock). Thus questions regarding the cause of the death of the Taung child cannot be answered with any certainty.