Human Resources

One thinks of running a fossil excavation as being a strictly scientific endeavor, but it is actually mostly management. An excavation leader has to organize permits, budgets, meals and lodging for students, payrolls for locally hired workers, and more. My late friend, the great Alun Hughes who found so many fossils at the fossil site of Sterkfontein, near Johannesburg, told me that running an excavation is more like being a farmer – you are always fixing equipment, planning rather than harvesting, and dealing with labor issues. Alun was right. Leading an excavation is a management position more than a scientific one. As an academic in anthropology, not business or political science, I made my share of mistakes. But this was never business as usual; it was perpetually business as unusual.

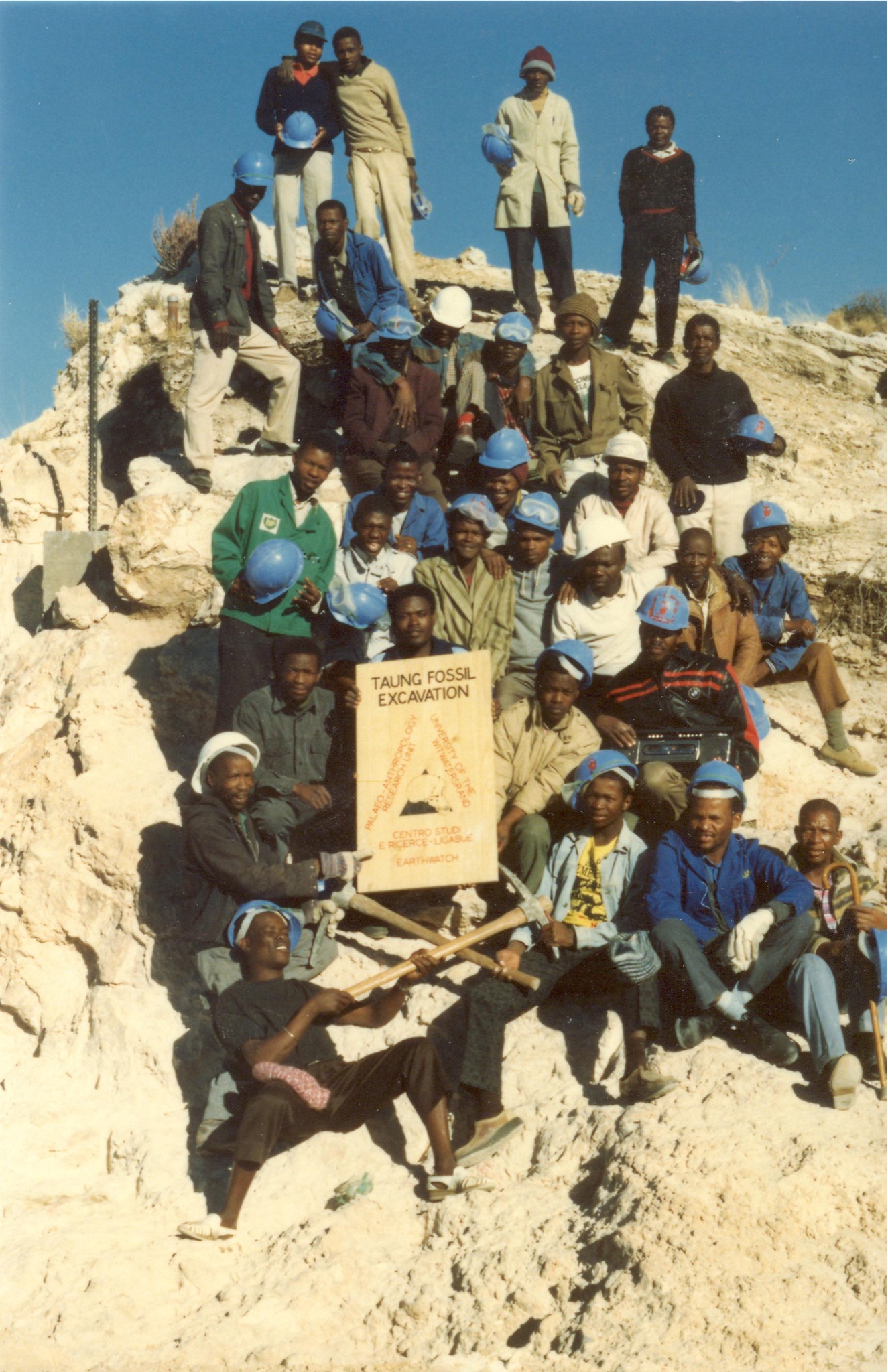

Labor at Buxton was always interesting. I had no previous experience in hiring and firing, but learned how to do it fairly quickly. Hiring was the fun part, but also came with some pains. At maximum I had 25 positions, and usually 90 plus applicants. I’d set up shop at the site early on a Monday, and entertain a long line of people, some at the brink of starvation. I would then do my best to hire those who could do the job, and speak English.

Once I had it down to an art, by the third year of field seasons, I’d ask each a series of questions. “What’s your name?” They’d give me their English first names and real surname ... more on that later. “Do you speak English?” They’d all say yes, even though some of them did not. Most of these people, with no formal education, spoke five or six languages beyond Setswana (the language of the Tswana people I was hiring); I was looking for those who could speak at least some English. “How old are you?” There the answer was almost always “29.” Somehow they figured that 29 was the ideal age to be. Young boys were 29. Old men were 29. No women of any age were in line.

Every now and then I’d mix up the questioning, however. They always got their name right, I think, but then: “How old are you?” “Yes.” “Do you speak English?” “29.” Others in the line who saw the ploy looked off into the sky, trying not to change their facial expressions or laugh out loud.

One year we had to wait a week for one of my better workers to be rehired after years of service. He was a muscular man who did a better baboon imitation than my own, but was always responsible and fun-loving on the site. The Bophuthatswana officials specifically let him out of jail to come work for me. I asked for the reason he was in jail. “Murder,” I was told. It turns out he killed somebody in a bar fight. “It wasn’t his fault,” I was reassured. Years later, after the excavation had ended, I was on a visit to Buxton and asked an old friend about him. “He’s a hair-dresser in Taung.” It turned out to be true, and one of the many ironies that still boggles my mind.

I lucked out and had a very bright team every year, for the most part. Despite their lack of formal education, they learned to recognize fossil bones, from the tiniest rodent tooth to more obvious long bones and skulls. Ah, the joy of one of them looking up with a smile, and saying proudly, “Mr. Jeff, I found a teeth!”

In order to manage the locally hired workers, I’d appoint a foreman from their ranks. It would be one who had shown responsibility and had a good command of the English language. For the first two years, it was Isaiha*, who was older than age 29 by his own admission and showed considerable wisdom. He worked hard too, so was a great leader in that respect.

In the mornings he would organize the men in gathering the equipment from the warehouse and taking it up the steep hill of limestone dust to the fossil site. I’d assign tasks and Isaiha would choose who he thought would work out best. It went smoothly for two field seasons. We would all gather at the warehouse at 8:00 am. Rarely was there a straggler because they all knew to be there at 8:00 sharp, or be chosen by Isaiha for one of the more onerous tasks.

One week we were going to be visited by the executive director of the Taung excavation, the venerable Professor Phillip V. Tobias (who you will see cited often in the Taung bibliography on this web site.) So I told Isaiha who was coming, and he knew the name. Tobias was legendary throughout South Africa not only for his scientific acumen, but for his leadership in the fight against apartheid. So Isaiha gathered together the excavation team, with myself and my graduate student, Wallace Scott, standing behind him. Isaiha said to his rapt audience, “You know there are three.” Everybody nodded their heads, many said “yaybo” (yes) while Wallace and I turned to each other confused, until I realized that Isaiha was referring to the Christian Holy Trinity.

Isaiha continued: “We have Mr. Wallace, and Mr. Jeff. Tobias is at the top.” The team all looked in wonderment while Wallace and I were left to debate who was Jesus and who was the Holy Spirit. But to many, Tobias always had that spiritual aura and it wasn’t lost on this crowd.

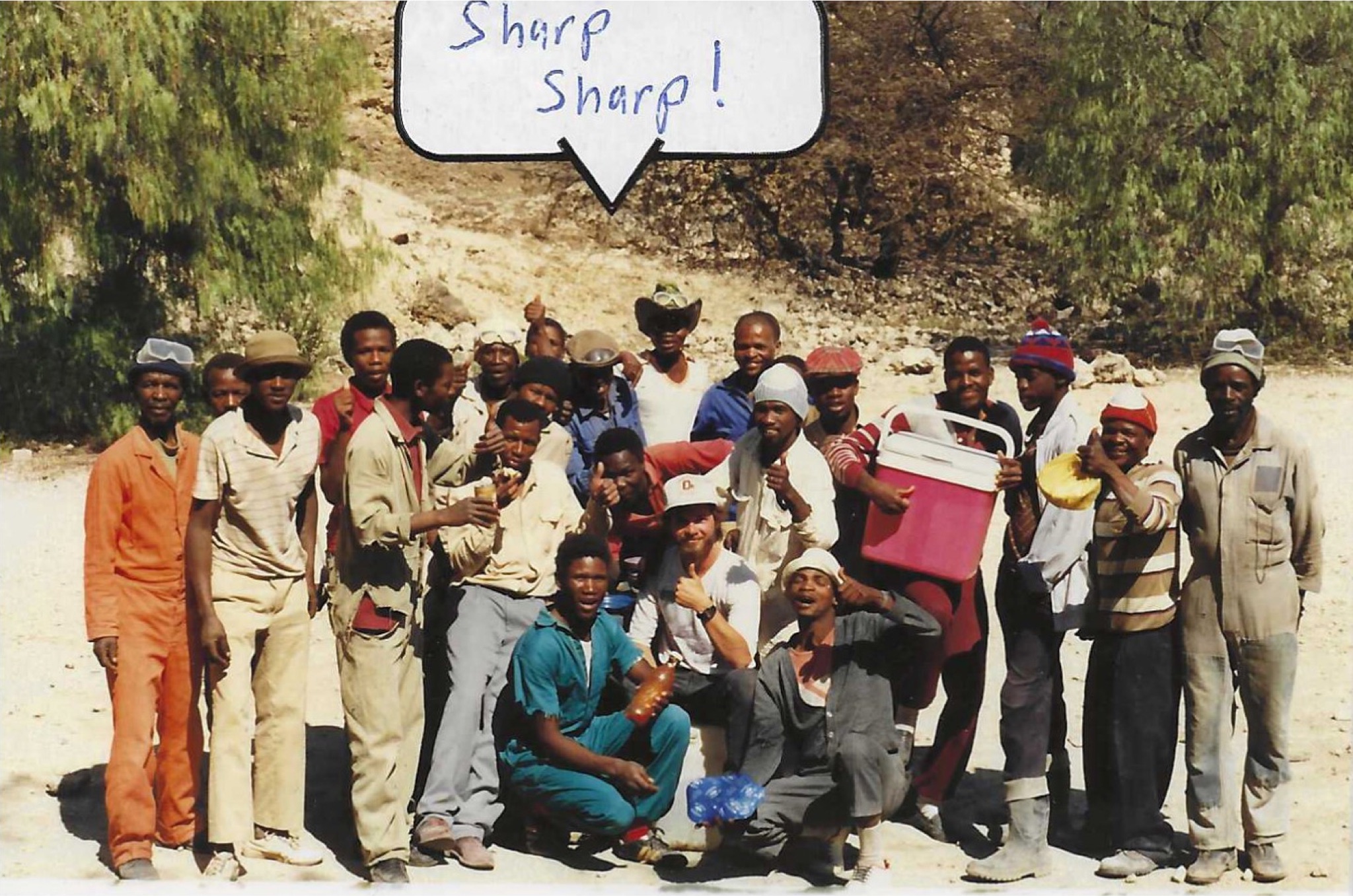

Daily starting time was an interesting point of discussion. The locals would often say “sharp” or “sharp, sharp” when something was good and cool. Because of their accents, I wasn’t sure whether they were saying “sharp” or “shop.” I asked them down at the warehouse and they clarified that it was “sharp.” I liked that, because as a youngster, “sharp” was the word I used for “cool.” But for fun, I told them that Americans used the word “groovy” instead of “sharp.” That afternoon, after we had taken the equipment back down to the warehouse, I reminded them that I wanted to see them the next day at 8:00 sharp. Some of them looked at me and said “Here at 8:00 groovy.” I just smiled inside.

Unfortunately, the warehouse turned out to be Isaiah’s downfall and the end of his two-year reign. Some of his coworkers snitched on him and told me that he had stolen equipment from the warehouse. When I checked it out, it was true. So it wasn’t easy for me, but I had to fire him. He had just gotten a little too heady, I guess. And that is the tough side of human resources.

I only had to fire one other person during the Taung excavation years, and that wasn’t as difficult. Daniel had never been more than an adequate worker, and he didn’t seem to be very popular with his colleagues. But we were out at the edge of the Kalahari Desert, and I didn’t expect perfection. Much less perfect was the day he came in completely drunk. He started the day off okay, at 8:00 groovy, but then his behavior became increasingly erratic. I suspect he was drinking on the job. So it was pretty easy to fire him on the spot and send him back down the hill to the Buxton village. But he wasn’t going without making a spectacle. So he shouted out, “Mr. Jeff, you are soooo stupid.” I said “Goodbye Daniel.” In unison, all of the other members of our team, without looking up from their work, said “Goodbye Daniel.” He shouted out another insult, and in unison, we all repeated “Goodbye Daniel.” This routine repeated one or two more times before he was gone down the hill from the fossil site. Apparently, nobody was sad to see him go.

The loss of Isaiha left me in a quandary the next year as to who to choose as the foreman. In the previous year, I had noted a young man, under age 29, who worked hard, had good rapport with the others, and spoke impeccable English. His name was Hamlet, and I gave him the job. That was a mistake on my part, because in Tswana culture, like in many cultures, the expectation was to put an older, more mature person in a position of authority. So some of the elders resented having this ‘kid’ telling them what to do. He did a great job, but I lost some respect from members of my team for making that choice. The next year, I rectified that by choosing Joseph Leeuw (his real name), and he was reliable to the point that I hired him to work in our fossil lab at the University in Johannesburg.

Finally, a note on names, as I promised earlier. Most of them used their English name, also known as a Christian name. Only one person, Bungane, used his first name. And it turns out that this name meant “show off,” and that fit him well because he had a bit of a boastful streak, but he had a good nature too, so I always laughed with him about it. But others who did use their English names were always a little curious about my name. This is because Jeff is a familiar name in their part of the world, as is Jeffers, my family name. A couple of my students and coworkers found that particularly odd, so I made the joke that I was called Jeff Jeffers in their honor.