Sharp, Sharp

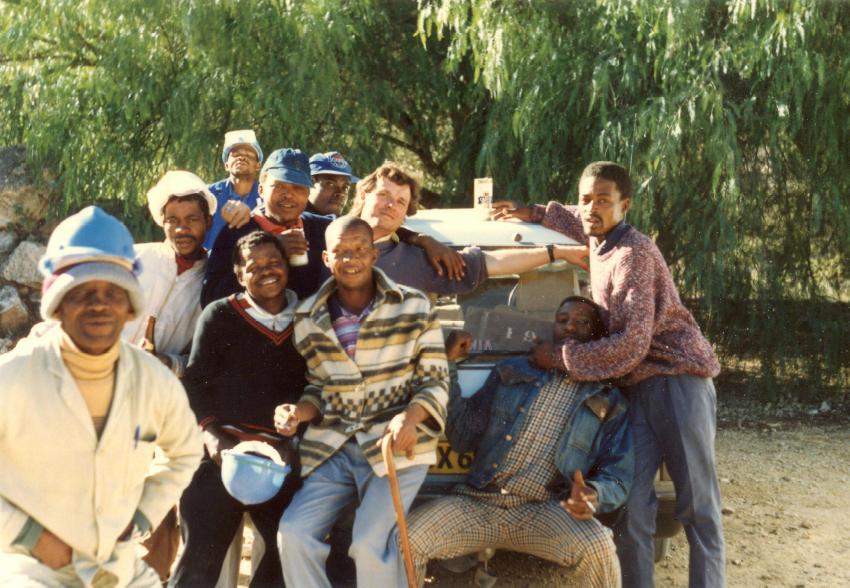

For most of my workers at Taung, English was a third or fourth language. It always amazed me that with little or no formal education, they could master so many different languages. Most were Setswana speakers first, and could speak fluently in the other African languages such as isiZulu. They could speak Afrikaans, the Dutch-based language that evolved from the early Cape settlers of southern Africa. And then came English.

We all learned to communicate, despite my relative ineptitude at their main language. I learned a few greetings, and words like “epa,” which means “dig.” One had to be careful, though. Most of the words I learned were from a Setswana/English dictionary that I had purchased in the Taung village’s bookstore, and it was a bit outdated. Moreover, I found that Setswana is quite variable. I once wrote a description of our work at Taung for a Bophuthatswana magazine that got translated into Setswana. I proudly handed copies of the article to those of my workers who could read, and they roundly rejected it. “Can we have the English version? This is Mmabatho Setswana, not our Setswana.” (Mmabatho was the capital of Bophuthatswana, in another section of this apartheid wasteland.)

But it was the greetings that turned out to be handy, and universal. “Dumela” means “hello” and “ke a la boga” means “thank you.” That wasn’t hard to learn. And learning some subtleties helped out a lot. For example, over the years I had become a patron of the local school. I arranged donations of books, and money, and even old microscopes from the Wits University anatomy department. The school was run by the wife of the local chief, and I’d occasionally pay her a visit at the school. On one of these visits she took me into a newly constructed classroom, built in part by money I helped raise, but mostly by the hands of the locals.

The classroom was full of children of various ages, all very curious about this strange man who had been ushered into their special place. Their faces lightened when I was introduced as “Mr. Jeff,” for they all knew about the commotion on the hill above the school at the limeworks. The chief’s wife, their principal, then said to me “Say something!” So I used the formal form of “dumela” (hello), used for addressing a group of respected people. “Dumeleng,” I said. The students immediately jumped to their feet and started applauding. It was the only one-word speech for which I got a standing ovation. (Well, the only standing ovation to this date as well.) Taken somewhat aback, I said “ke a la boga” (thank you), and their faces lit up with smiles and their hands gave more applause.

Appropriate words, however, do not always come so cheaply. On the occasion that I delivered the microscopes to the school, the principal decided we should have a ceremony. I thought she had a good idea, so I agreed. Ironically, I had recently read a fun book by a fellow anthropologist, Nigel Barley, who also wrote about his anthropological adventures in Africa. In it he said that one should never go into the field without a dress suit. I had heeded his advice, in part, and happened to at least have a jacket and tie with me, for the first and last time during my seven years of Taung adventures I dressed up. I was ready for the ceremony, or so I thought.

At the ceremony were the school principal, and her husband, the local chief. There were teachers and school children and local dignitaries, all sitting in chairs outside, next to the school. I had no clue who the master of ceremonies was, but he stood up and said: “we shall begin with a prayer from Mr. Jeff.”

Pregnant pause.

It suddenly occurred to me what he had said. I knew that these people were mostly Christian, but had a wide variety of beliefs. And I’m not the kind of person who regularly prays in public. Quite literally, I hadn’t a prayer. So I thought of what my older brother would have uttered, as he regularly does public prayer. I muddled something out, that even I can’t remember, and most of them probably couldn’t understand. God only knows what I said.

I had learned from the beginning that language could be tricky, because words can have so many meanings. On one of my early trips to Taung I encountered a group of Afrikaners who understood very little English. They directed me to the one person who spoke English, and he proudly stated: “Oh yes, I speak English very deliciously.” And like-sounding words can also be misused; I’m reminded of a German friend of mine who told me that after visiting an American home for dinner, she said “Thank you for your hostility!” (Meaning “hospitality,” obviously.)

But “sharp, sharp” was my favorite phrase frequented by the people of Taung. I’d ask our workers to do something, and “Sharp, sharp, Mr. Jeff” was their nearly universal reply. To my American ear, at first I thought they were saying “shop, shop.” So I asked them what they were saying, “sharp” or “shop”? When I got the answer, and an explanation that it meant “good,” I thought back to my youth in the late sixties and early seventies when I adopted the word “sharp” as an equivalent of “cool” or “groovy.”

So “sharp, sharp” fit right into my lexicon. Just for fun one morning, I told them that Americans often used the word “groovy” for what they meant by “sharp.” That took an interesting slant that afternoon. I had had trouble with some of them showing up late for work, so I told them that tomorrow they must be on site at eight o’clock sharp. “Okay, Mr. Jeff, we’ll be here at eight o’clock groovy.”

Copyright Jeffrey K McKee 2025